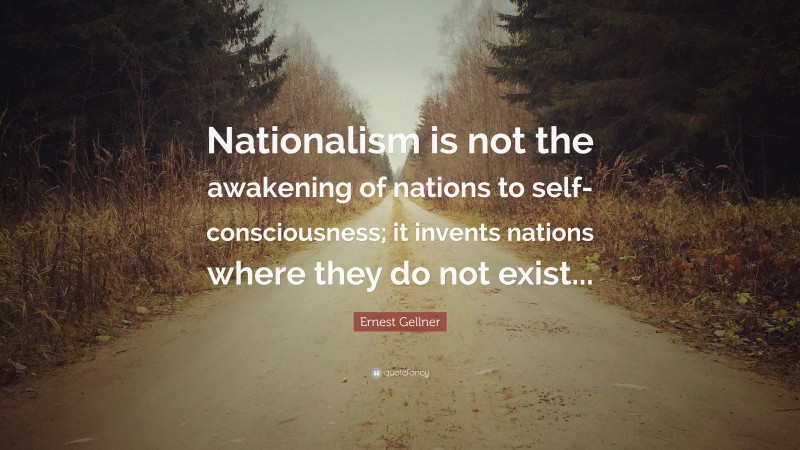

At the age of 17, he won a scholarship to Balliol College, Oxford, as a result of what he called "Portuguese colonial policy", which involved keeping "the natives peaceful by getting able ones from below into Balliol." In 1939, when Gellner was 13, the rise of Adolf Hitler in Germany persuaded his family to leave Czechoslovakia and move to St Albans, just north of London, where Gellner attended St Albans Boys Modern School, now Verulam School (Hertfordshire). This was Franz Kafka's tricultural Prague: antisemitic but "stunningly beautiful", a city he later spent years longing for. He was brought up in Prague, attending a Czech language primary school before entering the English-language grammar school. Gellner was born in Paris to Anna, née Fantl, and Rudolf, a lawyer, an urban intellectual German-speaking Austrian Jewish couple from Bohemia (which, since 1918, was part of the newly established Czechoslovakia). He is considered one of the leading theoreticians on the issue of nationalism. Among other issues in social thought, modernization theory and nationalism were two of his central themes, his multicultural perspective allowing him to work within the subject-matter of three separate civilizations: Western, Islamic, and Russian.

As the Professor of Philosophy, Logic and Scientific Method at the London School of Economics for 22 years, the William Wyse Professor of Social Anthropology at the University of Cambridge for eight years, and head of the new Centre for the Study of Nationalism in Prague, Gellner fought all his life-in his writing, teaching and political activism-against what he saw as closed systems of thought, particularly communism, psychoanalysis, relativism and the dictatorship of the free market. His first book, Words and Things (1959), prompted a leader in The Times and a month-long correspondence on its letters page over his attack on linguistic philosophy. Ernest André Gellner FRAI (9 December 1925 – 5 November 1995) was a British- Czech philosopher and social anthropologist described by The Daily Telegraph, when he died, as one of the world's most vigorous intellectuals, and by The Independent as a "one-man crusader for critical rationalism".

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)